Apple Should Have Same Confidentiality Rights As Attorneys, Priests

Technology companies know more about us than our loved ones, attorneys, or priests. To balance the availability of that information in matters of public safety, businesses should have a limited exemption from being required to provide such information.

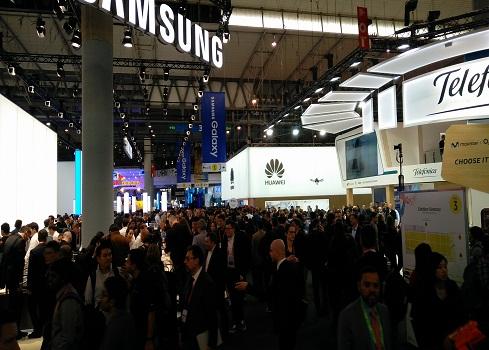

MWC 2016 Best In Show: Galaxy S7, LG's G5, More

MWC 2016 Best In Show: Galaxy S7, LG's G5, More (Click image for larger view and slideshow.)

FBI Director James Comey has spoken about the need for our legal system to balance public safety and privacy. But the US government's conception of balance is one-sided. The government has a right to force businesses to assist law enforcement operations, even if that work threatens privacy commitments made by businesses.

When every company becomes an on-demand informant, there's no balance. As Apple put it in a recent legal filing, the US government's interpretation of the All Writs Act is "boundless."

Apple's arguments against being forced to assist the FBI focus on the limits of the All Writs Act and on the company's rights under the US Constitution. The company also raises the issue of political reality. Any iPhone hacking software that Apple provides to the FBI will be demanded by other law enforcement agencies and by foreign governments.

But if as a society we're truly interested in balancing public safety and privacy, we should consider the application of testimonial privilege to third-party service providers.

Our legal system accepts that spouses, priests, and certain professions like accountants, attorneys, and physicians are exempt from having to testify in certain circumstances. Some jurisdictions recognize a parent's right not testify against a child.

These rights vary in different places and are not absolute, but they provide some measure of privacy where it serves the social good.

Businesses should have similar rights. In many cases, they know more about us than spouses. Apple's iPhones probably hear more confessions than priests. And, chances are, they remember everything.

Data may not be regarded as testimony, but in many ways it's the same thing. It's a testament to our conversations and actions. In Apple's case, the FBI wants the company to create code, which the courts have recognized as expressive speech.

Under the US government's interpretation of the All Writs Act, businesses must cooperate with law enforcement when assistance isn't an undue burden. But the government treats digital information too lightly, as if it were making a trivial demand on Apple.

Businesses should have the privilege not to inform on their customers unless they choose to do so, thereby allowing individuals to expect some measure of fidelity in their business relationships. Apple has helped law enforcement before and no doubt will again. But Apple needs to be able to provide assistance in a way that's consistent with its commitments. It needs to have the option to refuse, without being subject to sanctions or coercion.

[Read Microsoft, Facebook and Google Take Apple's Side in FBI Showdown.]

In this particular case the FBI has not demonstrated that the unknown data it hopes to obtain will have any value. Were the agency certain that an imminent terror attack could be thwarted with the data it seeks, its argument would be stronger. But it hasn't met that burden of proof.

Sometime over the past few decades the spread of the Internet and mobile devices put everyone under de facto surveillance. There's no balance in the current situation at all. Everyone partaking in modern connected society gets surveilled. Mobile phones ping cell towers or Stingrays, leaving records of our movements. Cloud service providers store personal communications and pictures. Automated license plate readers and RFID toll tags track the movement of vehicles. Network providers and search engines see the websites we visit, and merchants track our interests.

Business data has become an All-You-Can-Eat buffet for authorities. While that may be convenient for investigators, it makes a mockery of the concept of privacy. If there's to be any balance between security and privacy, businesses should have the right not to act as informers under all but the most extreme circumstances.

Are you an IT Hero? Do you know someone who is? Submit your entry now for InformationWeek's IT Hero Award. Full details and a submission form can be found here.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like

How to Amplify DevOps with DevSecOps

May 22, 2024Generative AI: Use Cases and Risks in 2024

May 29, 2024Smart Service Management

June 4, 2024